|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

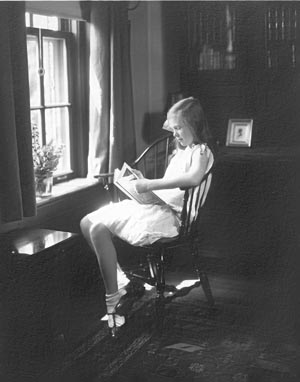

William Lyon Phelps speaks |

||||

|

|

||||

The habit of reading is one of the greatest resources of mankind; and we enjoy reading books that belong to us much more than if they are borrowed. A borrowed book is like a guest in the house; it must be treated with punctiliousness, with a certain considerate formality. You must see that it sustains no damage; it must not suffer while under your roof. You cannot leave it carelessly, you cannot mark it, you cannot turn down the pages, you cannot use it familiarly. And then, some day, although this is seldom done, you really ought to return it.

But your own books belong to you; you treat them with that affectionate intimacy that

annihilates formality. Books are for use, not for show; you should own no book that you

are afraid to mark up, or afraid to place on the table, wide open and face down. A good

reason for marking favorite passages in books is that this practice enables you to

remember more easily the significant sayings, to refer to them quickly, and then in later

years, it is like visiting a forest where you once blazed a trail. You have the pleasure

of going over the old ground, and recalling both the intellectual scenery and your own

earlier self.

Everyone should begin collecting a private library in youth; the

instinct of private property, which is fundamental in human beings, can here be cultivated

with every advantage and no evils. One should have one's own bookshelves, which should not

have doors, glass windows, or keys; they should be free and accessible to the hand as well

as to the eye. The best of mural decorations is books; they are more varied in color and

appearance than any wallpaper, they are more attractive in design, and they have the prime

advantage of being separate personalities, so that if you sit alone in the room in the

firelight, you are surrounded with intimate friends. The knowledge that they are there in

plain view is both stimulating and refreshing. You do not have to read them all. Most of

my indoor life is spent in a room containing six thousand books; and I have a stock answer

to the invariable question that comes from strangers. "Have you read all of these

books?"

"Some of them twice." This reply is both true and

unexpected.

There are of course no friends like living, breathing, corporeal men and women; my devotion to reading has never made me a recluse. How could it? Books are of the people, by the people, for the people. Literature is the immortal part of history; it is the best and most enduring part of personality. But book-friends have this advantage over living friends; you can enjoy the most truly aristocratic society in the world whenever you want it. The great dead are beyond our physical reach, and the great living are usually almost as inaccessible; as for our personal friends and acquaintances, we cannot always see them. Perchance they are asleep, or away on a journey.

But in a private library, you can at any moment converse with Socrates or Shakespeare or Carlyle or Dumas or Dickens or Shaw or Barrie or Galsworthy. And there is no doubt that in these books you see these men at their best. They wrote for you. They "laid themselves out," they did their ultimate best to entertain you, to make a favorable impression. You are necessary to them as an audience is to an actor; only instead of seeing them masked, you look into their innermost heart of heart."

William Lyon Phelps - 1933

Home